- Remove the current class from the content27_link item as Webflows native current state will automatically be applied.

- To add interactions which automatically expand and collapse sections in the table of contents select the content27_h-trigger element, add an element trigger and select Mouse click (tap)

- For the 1st click select the custom animation Content 27 table of contents [Expand] and for the 2nd click select the custom animation Content 27 table of contents [Collapse].

- In the Trigger Settings, deselect all checkboxes other than Desktop and above. This disables the interaction on tablet and below to prevent bugs when scrolling.

My nonna outlived my nonno by ten years.

For a long time, I thought those extra years were purely a gift. More time with her grandchildren. More stories. More of her presence in our lives during holidays and Sunday dinners.

And in many ways, they were a gift. But they were also harder than anyone had prepared us for. She spent those years navigating a cognitive decline that felt different from what we'd seen with him. Sharper drops. Longer stretches of confusion. More years where she was physically present but not quite herself.

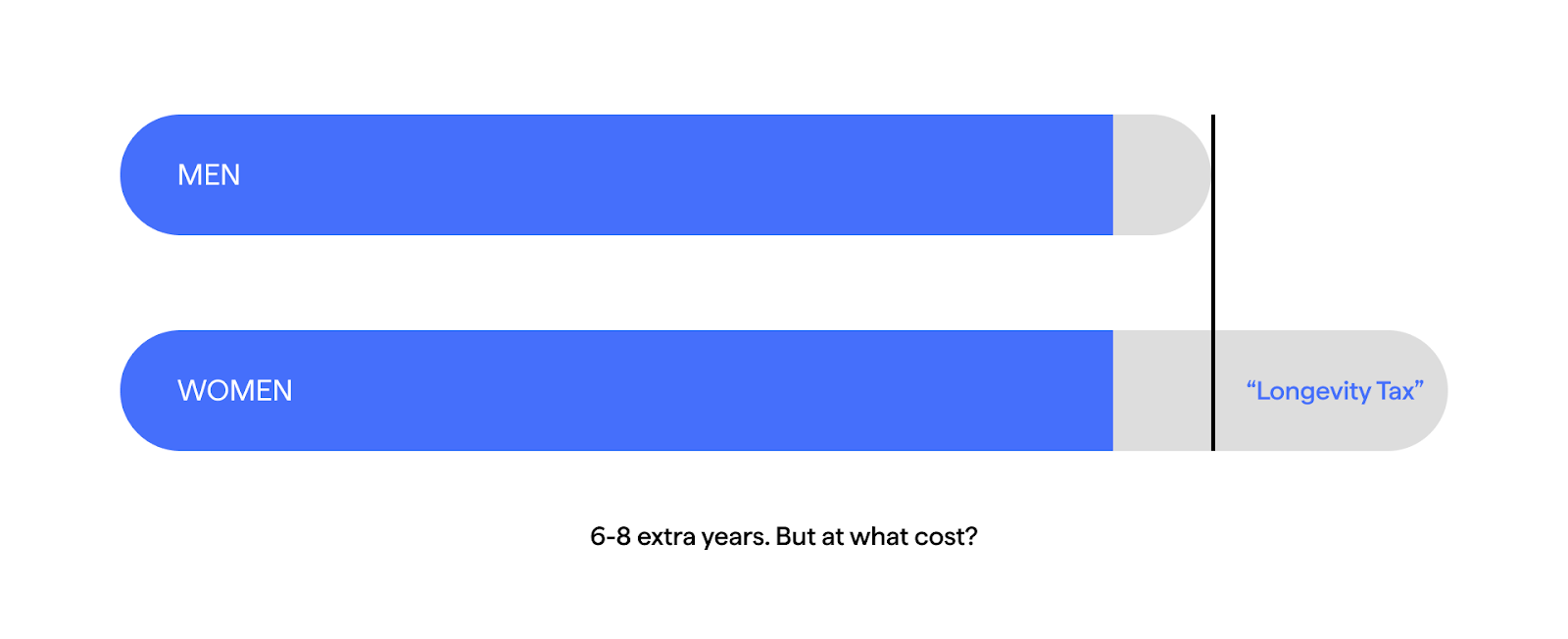

Women live longer than men - six to eight years longer on average. We've been told this is winning. That longevity is the ultimate health outcome, the thing we should all be optimizing for.

But here's what nobody mentions: women aren’t just living longer. They’re living more of those years with cognitive decline and dementia.

Two-thirds of Alzheimer's patients are women. And before you think "well, of course, women just live longer," even when you control for lifespan, women are still at higher risk

Women aren’t winning the longevity game. They just got handed extra years without anyone building the infrastructure to make them good years.

That's not a victory. That's a tax.

The prize nobody wanted

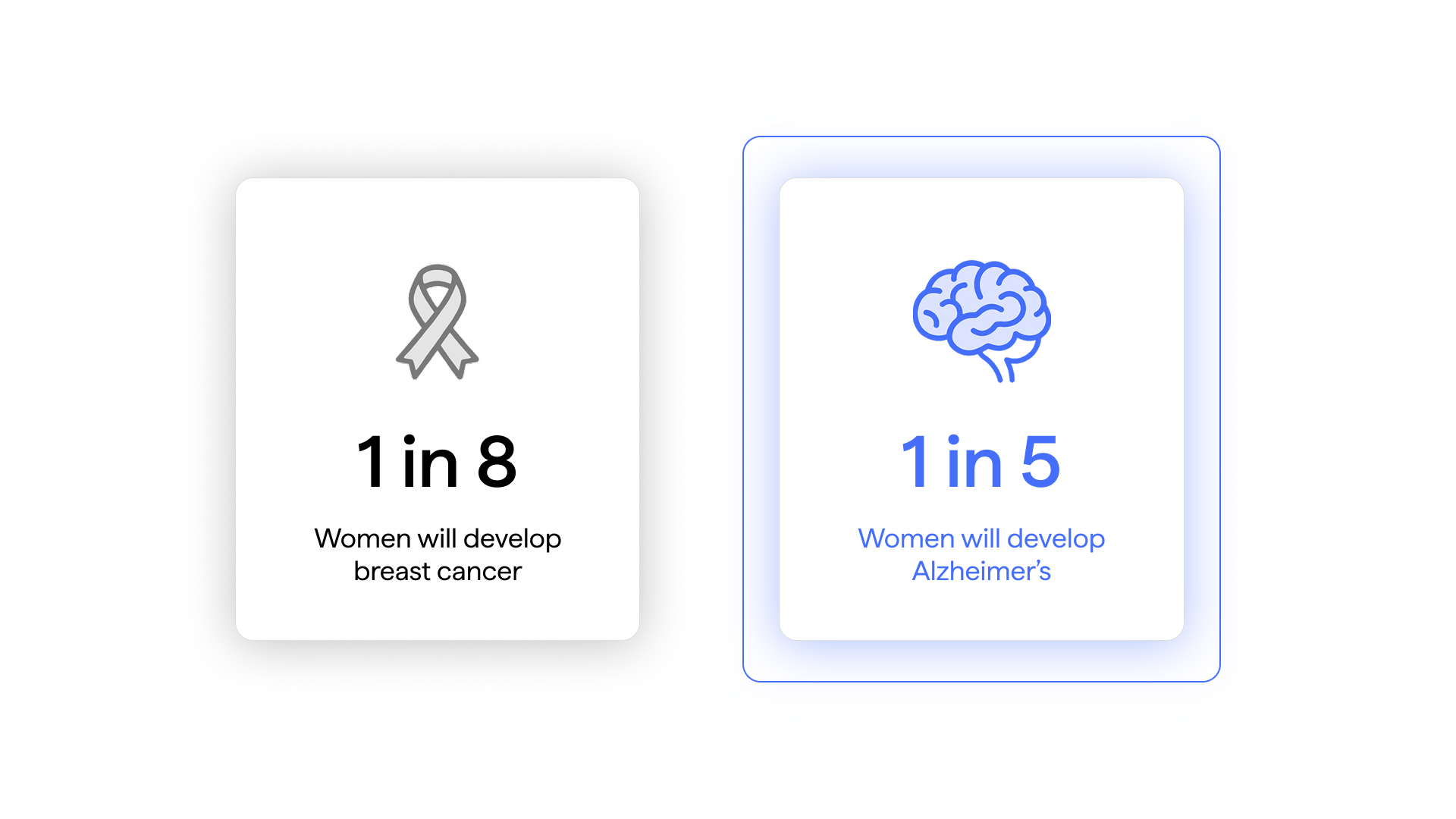

Let me put this in perspective: As a woman, you're more likely to develop Alzheimer's than breast cancer. Twice as likely, actually.

But we've all seen the pink ribbons. Done the walks. Shared the awareness posts. Breast cancer receives hundreds of millions in dedicated research funding annually and has become a massive public health priority - as it should be.

Meanwhile, even though Alzheimer's research funding has increased dramatically in recent years to nearly $4 billion annually, the portion dedicated specifically to understanding why two-thirds of patients are women remains a tiny fraction. The Women's Alzheimer's Movement - one of the few organizations focused specifically on women and Alzheimer's - has awarded about $6 million total across all their grants. That's roughly 0.15% of annual Alzheimer's funding, for a disease where women are the majority of patients.

Women are not just living longer. They are living more of those years losing themselves.

Following the wrong map

A friend of mine, Sarah, who gave me permission to share this, turned 62 this year. She's one of those people who's been doing everything right for decades. Daily exercise since her 30s. Mediterranean diet. Omega-3s, good sleep, crossword puzzles, strong social connections. The whole longevity playbook.

Last year, she started noticing things. Nothing dramatic - just that conversations felt harder to follow. She'd lose her train of thought mid-sentence. Her processing speed felt... slower.

So she did what you're supposed to do: she went to her doctor.

He ran the standard cognitive tests. Everything came back fine. "Normal aging," he said. "You're doing all the right things. Keep it up."

But Sarah's a researcher by training. And something about that answer bothered her. If she was doing "all the right things," why was she noticing changes? Were the changes even real? Should she be worried? Should she be doing something different?

She went through menopause at 53. Nearly a decade ago. She'd had some brain fog during the transition - who doesn't? - but it had seemed to clear up after a year or two. This felt different. More persistent.

She started digging into the research behind all those "right things" she'd been doing for thirty years.

That's when she found it.

The exercise protocols that supposedly reduce dementia risk? Predominantly studied in men. The Mediterranean diet evidence? Most of the landmark trials had far more men than women. The cardiovascular interventions we're told to protect our brains - the ones that shaped current treatment guidelines? Some were conducted on 15,000 men, 22,000 men, with zero women.

Women made up less than 40% of participants in cardiovascular trials between 2010 and 2017.

Sarah had been meticulously following a roadmap that was never actually drawn for someone like her. For someone planning to live to 90, not 78. For someone whose cardiovascular risk spikes after menopause. For someone whose brain metabolizes glucose differently during hormonal transitions.

She'd done everything right, according to research that never included her in the first place.

"I felt like I'd been scammed," she told me. "Not by my doctor. Not even by the researchers, really. But by a system that somehow decided women's brains weren't important enough to study properly."

The window that doesn't exist

Sarah went back to her doctor armed with questions. Could they establish a baseline? Run more comprehensive testing? Monitor her cognitive function over time so they'd have data if things changed?

No, she was told. Insurance won't cover that. There's no protocol for monitoring cognitive health in healthy adults. Come back if symptoms get worse.

"So I'm supposed to just... wait?" she asked. "Wait until I have dementia to start paying attention to my brain?"

Essentially, yes.

Here's what makes this especially cruel: research suggests the best window for intervention is during perimenopause and early menopause, right when women are most likely to notice cognitive changes. Right when the brain undergoes massive metabolic shifts, glucose utilization drops, and brain volume in critical memory regions decreases up to 30% faster in women than in men.

That was nine years ago for Sarah. When she was 53, experiencing brain fog, maybe noticing the first signs of metabolic changes in her brain. That was the moment. That was when someone should have been paying the closest attention.

Instead, like most women, she was told it was "just menopause." Temporary. Normal. Nothing to worry about.

Now she's in her early 60s. If she develops Alzheimer's in her 70s or 80s - and as a woman, her odds are higher than she probably realizes - she'll have missed twenty to thirty years of potential intervention. Twenty to thirty years where she could have been tracking, adjusting, optimizing.

We don't wait until we have heart disease to start caring about cardiovascular health. We don't wait until we have diabetes to start monitoring blood sugar.

Why are we waiting until we have dementia to start caring about our brains?

What now?

I'm not sharing Sarah's story to catastrophize. I'm sharing it because she shouldn't have had to become her own researcher to get basic answers about her brain health.

None of us should.

The future isn't just about living longer. It's about living those extra years sharp, engaged, still ourselves. Still making memories instead of losing them. Still fully present with the people we love.

Women are at the center of the Alzheimer's epidemic. We're the majority of patients, the majority of caregivers, and we've been systematically left out of the research that could change the trajectory of this disease.

We didn't create this problem.

But we can refuse to accept it.

Sarah is tracking what she can now—paying attention and advocating for herself loudly enough that her doctor has finally agreed to establish a cognitive baseline. She's not waiting for permission anymore.

The longevity tax isn't inevitable. But paying attention? Demanding better? That part is up to us.

Citations:

Two-thirds of Alzheimer's patients are women:

- Alzheimer's Association. (2025). 2025 Alzheimer's Disease Facts and Figures. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/facts-figures

- Alzheimer's Association. Women and Alzheimer's. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers/women-and-alzheimer-s

Women twice as likely to develop Alzheimer's as breast cancer:

- Alzheimer's Association. Women and Alzheimer's. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers/women-and-alzheimer-s

Women live 5-8 years longer than men:

- Our World in Data. (2021). Why do women live longer than men? https://ourworldindata.org/why-do-women-live-longer-than-men

- USAFacts. Do women live longer than men in the US? https://usafacts.org/articles/do-women-live-longer-than-men-in-the-us/

- TIME. (2023). U.S. Women Now Live About 6 Years Longer Than Men. https://time.com/6334873/u-s-life-expectancy-gender-gap/

Even controlling for lifespan, women are at higher risk:

- Harvard Health. (2022). Why are women more likely to develop Alzheimer's disease? https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/why-are-women-more-likely-to-develop-alzheimers-disease-202201202672

- Beam, C.R., et al. (2018). Differences Between Women and Men in Incidence Rates of Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 64(4):1077–1083. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6226313/

Alzheimer's funding reaches nearly $4 billion annually:

- National Institute on Aging. (2024). NIH's Alzheimer's Disease and Related Dementias FY 2024 Bypass Budget. https://www.nia.nih.gov/research/blog/2022/07/looking-forward-nihs-alzheimers-disease-and-related-dementias-fy-2024-bypass

- Alzheimer's Impact Movement. (2024). Congress Reaches Bipartisan Agreement on $100 Million Alzheimer's Research Funding Increase. https://www.alz.org/news/2024/congress-reaches-bipartisan-agreement-research-funding-increase

Women's Alzheimer's Movement grants (~$4-6 million):

- Women's Alzheimer's Movement at Cleveland Clinic. About Us. https://thewomensalzheimersmovement.org/about-us/ (States: "funding over $4 million in seed grants")

- Women's Alzheimer's Movement at Cleveland Clinic. Research. https://thewomensalzheimersmovement.org/research-2/ (States: "funded $4.65 million for 44 studies")

Women made up less than 40% of cardiovascular trial participants (2010-2017):

- Jin, X., et al. (2020). Women's Participation in Cardiovascular Clinical Trials From 2010 to 2017. Circulation, 141:540–548. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.043594

Brain glucose metabolism decline and volume changes during menopause:

- Mosconi, L., et al. (2021). Menopause impacts human brain structure, connectivity, energy metabolism, and amyloid-beta deposition. Scientific Reports, 11:10867. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-90084-y

- Weill Cornell Medicine. (2021). Imaging Study Reveals Brain Changes During the Transition to Menopause. https://news.weill.cornell.edu/news/2021/06/imaging-study-reveals-brain-changes-during-the-transition-to-menopause

Brain metabolic shifts and glucose utilization:

- Yin, F., et al. (2015). Transitions in metabolic and immune systems from pre-menopause to post-menopause: implications for age-associated neurodegenerative diseases. F1000Research. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6993821/

- Yao, J., et al. (2013). Early Decline in Glucose Transport and Metabolism Precedes Shift to Ketogenic System in Female Aging and Alzheimer's Mouse Brain. PLOS ONE. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0079977

Brain volume changes specific to menopause:

- The Menopause Society. (2025). How Menopause Restructures a Woman's Brain. https://menopause.org/press-releases/how-menopause-restructures-a-womans-brain

- Rahman, A., et al. (2023). Brain volumetric changes in menopausal women and its association with cognitive function: a structured review. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/aging-neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnagi.2023.1158001/full

2 Distraction Stroop Tasks experiment: The Stroop Effect (also known as cognitive interference) is a psychological phenomenon describing the difficulty people have naming a color when it's used to spell the name of a different color. During each trial of this experiment, we flashed the words “Red” or “Yellow” on a screen. Participants were asked to respond to the color of the words and ignore their meaning by pressing four keys on the keyboard –– “D”, “F”, “J”, and “K,” -- which were mapped to “Red,” “Green,” “Blue,” and “Yellow” colors, respectively. Trials in the Stroop task were categorized into congruent, when the text content matched the text color (e.g. Red), and incongruent, when the text content did not match the text color (e.g., Red). The incongruent case was counter-intuitive and more difficult. We expected to see lower accuracy, higher response times, and a drop in Alpha band power in incongruent trials. To mimic the chaotic distraction environment of in-person office life, we added an additional layer of complexity by floating the words on different visual backgrounds (a calm river, a roller coaster, a calm beach, and a busy marketplace). Both the behavioral and neural data we collected showed consistently different results in incongruent tasks, such as longer reaction times and lower Alpha waves, particularly when the words appeared on top of the marketplace background, the most distracting scene.

Interruption by Notification: It’s widely known that push notifications decrease focus level. In our three Interruption by Notification experiments, participants performed the Stroop Tasks, above, with and without push notifications, which consisted of a sound played at random time followed by a prompt to complete an activity. Our behavioral analysis and focus metrics showed that, on average, participants presented slower reaction times and were less accurate during blocks of time with distractions compared to those without them.

.webp)